In chapter four of my new book,  where I present my undiagnosed credentials for being on the spectrum, one of the characteristics of autism that I use to for that is repetitive behavior, which includes reading books again and again. I’ve read many novels three times or more.

where I present my undiagnosed credentials for being on the spectrum, one of the characteristics of autism that I use to for that is repetitive behavior, which includes reading books again and again. I’ve read many novels three times or more.

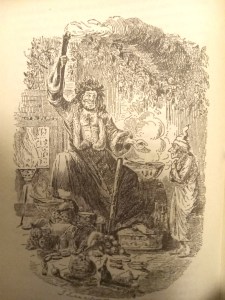

What I don’t say is that there is one novel that I’ve read at least 12 times – Charles Dickens’s The Christmas Carol.

Did you know that the story of Dickens’s most famous character, Ebenezer Scrooge, was so popular when it was first published on December 19, 1843, that several stage versions were quickly produced. Dickens himself, who was an actor as well as an author, took the stage in one of them.

Most of the literary experts insist on calling the book a novella, because it has only 93 pages (in my Penguin paperback) For me, being or not being a novel depends more on the content of a story than on how many pages you can count.

What fictional character has received more attention than Scrooge? What other story has had over 100 films made from it?

What I want to call attention to here is the opening of the novel. I consider the first page and a half of The Christmas Carol as a candidate for one of the best openings of a novel ever. Look at the first paragraph:

Marley was dead to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker,and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was dead as a door-nail.

This startling introduction, so tight and apparently simple, is the first of the story’s many jewels. Dickens could write long, complex, flowery paragraphs too, the kind that have become popular again today. But in a long paragraph of Dickens, as with Shakespeare, there was at least much to be found – in today’s 500-700 page novels those paragraphs are so often just piles of words, the author showing off their vocabulary, confident that readers believe that the more words you can throw at something the better a writer you are.

Short sentences are not as easy to produce as they look. If I had never read the story before, and I didn’t know who was writing it, the opening sentence above, and the last sentence, would be evidence to me that a genius was at work.

But let’s continue. After a brief paragraph wondering about the origin of the enigmatic phrase, ‘dead as a door-nail’ (a phrase I’ve loved since I was a boy – in the working-class steel town where I grew up in the 1950’s it was still in use), then three more short paragraphs explaining the business partnership of Scrooge and Marley, we get this description of Scrooge himself:

Oh! But he was a tightfisted hand at the grindstone, Scrooge! A squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster.The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and on his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dog-days; and didn’t thaw it one degree at Christmas.

There you have it. In one and a half pages, you’ve got the core of the plot slyly introduced, and a physical/psychological portrait of the central character that might be the best first description of one in all fiction.

A Christmas Carol was Dickens’s gift to the world that year. It has come back to us every Christmas since, and will continue returning in the future, because, I believe, it has achieved immortality.

This makes me want to read more of Dickens’s novels. I read Great expectations in university and thought it was pretty good. I’d also like to read more Thomas Hardy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dickens’s personal favorite was David Copperfield, and maybe it’s my favorite too.

LikeLike